'IS Brides' Open Up In Syria Camp Documentary At SXSW

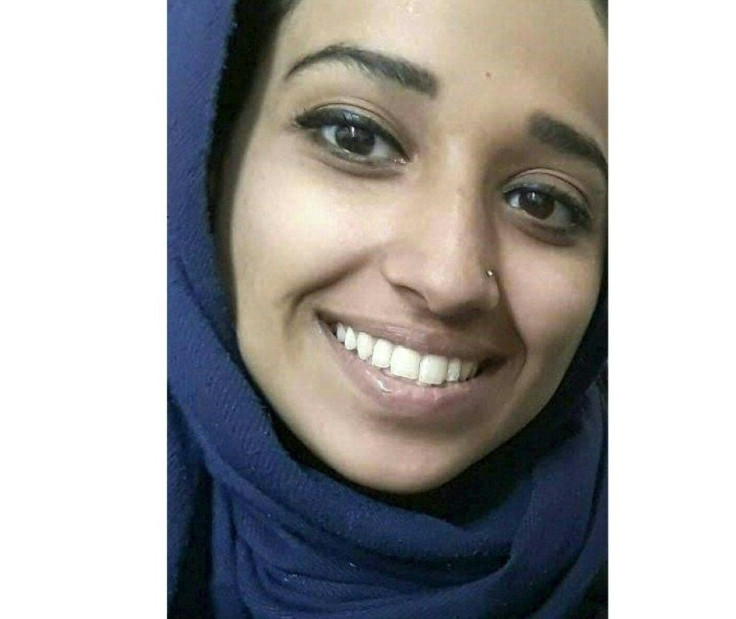

"Okay, um... My name's Shamima. I'm from the UK. I'm 19."

Spoken with a nervous laugh, the introduction to a room full of women and restless babies could be the start of any young mothers' support group.

But the speaker is Shamima Begum, the teenage "ISIS bride" who left Britain for Syria in 2015 to join the Islamic State group, and whose desire to return sparked a right-wing press frenzy that saw her stripped of her citizenship.

The footage is captured in "The Return: Life After ISIS," a documentary premiering Wednesday at the online Texas-based South By Southwest festival.

Spanish director Alba Sotorra got rare, extensive access to Begum and other Western women over several months in Syria's Kurdish-run Roj camp, where they remain following the so-called caliphate's collapse in 2019.

"I would say to the people in the UK, give me a second chance because I was still young when I left," Begum tells the filmmakers.

"I just want them to put aside everything they've heard about me in the media," she adds.

Begum left her London home aged just 15 to travel to Syria with two school friends, and married an IS fighter.

She was "found" by British journalists, heavily pregnant at another Syrian camp, in February 2019 -- and her apparent lack of remorse in initial interviews drew outrage.

But Begum and fellow Westerners including US-born Hoda Muthana strike a very different and apologetic tone in Sotorra's film.

The documentary follows "workshop" sessions in which the women write letters to their younger selves expressing regret about their departures for Syria, and plant a tree to remember their loved ones.

"It was known that Syria was a warzone and I still travelled into it with my own children -- now how I did this I really don't know looking back," says one Western woman.

Begum recalls feeling like an "outsider" in London who wanted to "help the Syrians," but claims on arrival she quickly realized IS were "trapping people" to boost the so-called caliphate's numbers and "look good for the (propaganda) videos."

Sotorra, the director, gained camp access thanks to Kurdish fighters she had followed in Syria for her previous film.

She set out to document the Kurdish women's sacrifices in running a camp filled with their former enemies' wives and children, but soon pivoted to the Western women.

"I will never be able to understand how a woman from the West can take this decision of leaving everything behind to join a group that is committing the atrocities that ISIS is committing," Sotorra told AFP.

"I do understand now how you can make a mistake."

On Sotorra's arrival in March 2019, the women -- fresh from a warzone -- were "somehow blocked... not thinking and not feeling."

"Shamima was a piece of ice when I met her," Sotorra told AFP.

"She lost the kid when I was there... it took a while to be able to cry," she recalled.

"I think it's just surviving, you need to protect yourself to survive."

Another factor is the enduring presence of "small but very powerful" groups of even "more radicalized women" who remain loyal to IS and exert pressure on their campmates.

"We had (other) women who joined in the beginning, and then they received pressure from other women so they stopped coming," said Sotorra.

In the film, Begum claims she "had no choice but to say certain things" to journalists "because I lived in fear of these women coming to my tent one day and killing me and killing my baby."

The question of what can and should be done with these women -- and their children -- plagues Western governments, sowing divisions among allies.

Last month, Britain's Supreme Court rejected Begum's bid to return to challenge a decision stripping her citizenship on national security grounds.

How much the women knew about -- and abetted -- IS's rapes, tortures and beheadings may never be known.

In the documentary, Begum denies she "knew about" or "supported these crimes," dismissing claims she could have been in IS's feared morality police as a naive "15-year-old with no Islamic knowledge" who did not even "speak the language."

"I never even had a parking ticket back in my own country before... I never harmed anybody, I never killed anybody, I never did anything," says Canadian Kimberly Polman.

An incredulous Kurdish woman points out that "maybe your husband killed my cousin."

Sotorra believes the women could be useful back home in preventing the same mistake in future generations, and points to the cruelty of raising young children in this environment.

"It took them a while to realise that they have responsibility for (their) choice... they cannot just think 'Okay, I regret, I go back, as if nothing has happened,'" she said.

"No, it's not about this... you have to accept the consequences."