Freed Putin Critic Recounts 'Miracle' Release In Historic Swap

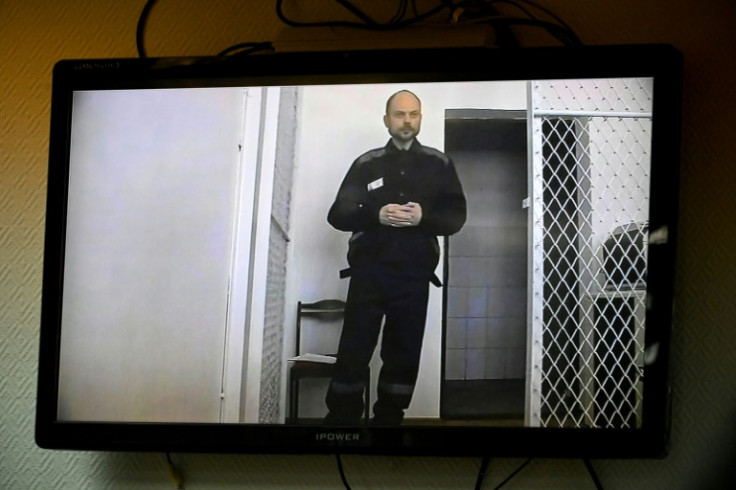

It has been around six weeks since Vladimir Kara-Murza swapped his prison long-johns and rubber flip flops for sharp suits, but the major opponent of the Kremlin says he is still adjusting to reality.

Kara-Murza was on August 1 released in the largest East-West prisoner swap since the Cold War, along with 15 other Russian dissidents and foreign nationals. He had been serving a 25-year sentence on treason and other charges after denouncing Moscow's invasion of Ukraine.

"Well, you know, something like this doesn't go without consequences," Kara-Murza told Agence France-Presse in an interview this week, carefully choosing his words.

"It is, of course, going to be a process to transition back into normal life, to transition back into normal work."

Kara-Murza was twice nearly killed by poisoning for his activism even before being jailed and lost 25 kilograms (55 pounds) during his imprisonment. He looked gaunt and malnourished when he was released and flown to Germany as part of the swap.

Since his release, he has met with US leader Joe Biden, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and French President Emmanuel Macron, but Kara-Murza says everything still feels "completely surreal."

During a meeting with AFP in Paris, Kara-Murza, who just celebrated his 43rd birthday, looked thin but healthy.

"Up until a few weeks ago I was absolutely certain that I was going to die in that Siberian prison, and everything that's happened with this exchange feels like a miracle, and it is a miracle."

But the ordeal has marked him forever.

He spent more than two years in Russian prisons including the Omsk maximum security penal colony IK-6.

"I was in solitary confinement for 11 months straight, without stop, without pause," he said.

He would wake up, attach his bunk to the wall at 5:00 am, and spend his days walking in a circle in a tiny, two-by-three-metre cell with a small, barred window under the ceiling or trying to sit at a small stool sticking out of the wall.

He was allowed to read and write for 90 minutes a day. There was nothing else to do, no one to speak to, nowhere to go.

"This is how you live day after day, week after week, month after month."

Kara-Murza said he understood from experience why solitary confinement lasting for more than 15 days is considered a form of torture according to international law.

"It is not very easy for a human being to, well, let me put it bluntly, to just stay sane in those circumstances," he said.

One day he heard the name of jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny on the radio. It was a Friday evening, and the brief announcement said that Vladimir Putin's top enemy had suddenly died in his remote Arctic prison.

The news was so horrible and Kara-Murza's conditions so miserable, he began to think he had "sort of imagined it."

He was in solitary confinement and spent the weekend in "a total vacuum", with no visits from lawyers and no letters from supporters.

"I don't think I have the words to describe the feeling," he said.

"After months and months in solitary confinement, your mind starts playing tricks on you."

Kara-Murza was deprived of regular contact with his family and other prisoners and was not allowed to go to church. But faith in God, knowledge of history and moral convictions sustained him.

"I know that everything in the end will be decided by Him," he said.

The 43-year-old, a joint Russian-UK national who studied at Cambridge, also sought solace in history.

"Nothing is new, and we have seen all of this in Russia before," he said.

He thought about Soviet dissidents who resisted the authorities before him, including Vladimir Bukovsky, who was exchanged for Chilean Communist leader Luis Corvalan in 1976.

Many years ago Kara-Murza, then a young journalist, was making a documentary film about the Soviet dissident movement, and he asked Bukovsky what helped him survive in detention.

"He responded very simply. He said: 'I knew that I was right.'"

Two decades later Kara-Murza truly understood what Bukovsky meant, having personally gone through a similar ordeal.

"I knew that I was right every minute of every day that I spent in prison," he said.

The days leading up to the prisoner swap were bizarre.

On July 23, he was sitting in his cell alone when two prison officers arrived and escorted him into a prison office with a big portrait of Putin on the wall.

He was asked to write a request for a pardon, but he refused, dismissing it as a joke.

"But they didn't seem to be in the mood for laughing," Kara-Murza said. "Generally, most people in the Russian prison system don't have a very good sense of humour."

The opposition politician said he would never ask Putin for a pardon, telling the prison officials he considered him "a usurper, a dictator, and a murderer."

He was invited to put those words on paper, which he happily did.

"Nobody explained why this was happening, because in all my two-plus years in prison, nobody's ever suggested that I write anything like this," he said.

On July 28, he was suddenly woken up by a loud noise in the middle of the night. The doors of his cell burst open, and a group of officers barged in.

It was 3:00 am and they told Kara-Murza he had 10 minutes to get ready.

"I was absolutely certain that I was going to be let out and be executed," he said.

Instead, he was taken to the Omsk airport, in handcuffs. The terminal was bursting with people.

"After months and months and months in solitary confinement when I could not as much as say hello to anyone, to suddenly find myself in the middle of a busy passenger airport with people, families with kids, cafes and shops open, it was mind-boggling."

He was bundled onto a plane and sent to Moscow, accompanied by a prison convoy.

"Nobody explained what was going on," he said.

Three hours later another prison convoy picked him up in Moscow and put him into a prison van.

When he was finally told to get out, he realised he had been brought to Russia's most infamous prison, Lefortovo, which over the years held dissidents such as Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Natan Sharansky and Bukovsky.

Kara-Murza demanded that his family and lawyers be notified of his transfer.

"Vladimir Vladimirovich, you have not been transferred to Moscow," one of the FSB officers told him, smiling. "You are still in Omsk."

Kara-Murza had given up trying to understand what was going on. Perhaps they wanted to open a new criminal case against him, he thought.

He was placed in a solitary confinement cell, which he said felt "like a five-star hotel" after his Omsk colony.

"Here I had a bed in which I could lie. Nobody cared. I had as many books as I wanted. I could write."

For several days he was held incommunicado.

Then came August 1. A group of officers led by the deputy director of Lefortovo walked into his cell with his bags from the storage. He was told to put his civilian clothes on and escorted down to the ground floor.

"There's a row of men standing, their faces covered in black masks and balaclavas. It was a pretty intimidating sight, like a scene out of some kind of a Hollywood action movie," he said.

Then, in the prison courtyard he saw a bus. He was told to get on board.

"And in there, I see in every row more men, more FSB operatives in black balaclavas," he said.

Next to them, Kara-Murza saw his friends and fellow political prisoners who had been serving time in different regions across Russia.

First he saw rights campaigner Oleg Orlov, who publicly compared Putin's rule to a fascist regime.

"That was the moment I knew what was happening," said Kara-Murza.

Another fellow Kremlin critic, Ilya Yashin, was on the bus as well. Yashin told Kara-Murza he looked bad.

"I said, yeah, thanks for the compliment. That was our first exchange."

They were all taken to Vnukovo Airport. The prisoners were glued to the windows.

"I was just looking at Moscow. Moscow is my hometown. I love my city," said Kara-Murza.

"Obviously, I realized that it would be a while before I'd be able to see it again."

Then the prisoners were bundled onto a government plane, escorted by the FSB operatives.

On the plane the FSB operatives became more relaxed and the prisoners were able to speak to each other.

Several hours later the plane landed in Ankara, and the historic prisoner swap took place on the tarmac.

Sixteen dissidents and Westerners including Wall Street Journal reporter and former AFP correspondent Evan Gershkovich were exchanged for eight Russian nationals, including a convicted hitman, and two minors.

Thirteen of the detainees freed by Russia, including Kara-Murza, went to Germany and three to the United States.

Later that evening Kara-Murza met with Chancellor Olaf Scholz, wearing the only clothes he had -- his black long-johns, black T-shirt and rubber flip flops.

© Copyright AFP 2025. All rights reserved.