How will history understand the hipster?

Last week, anti-gentrification protesters took to the streets of London’s East End as part of a series of parades organised by the anarchist group Class War.

One of their targets, the Cereal Killer Cafe, was bombed with paint and scrawled with graffiti that read “scum”. While businesses such as this one are a symptom of the city’s extreme gentrification, rather than its cause, they have - in the eyes of some - become symbolic of this rampant and unwelcome redevelopment.

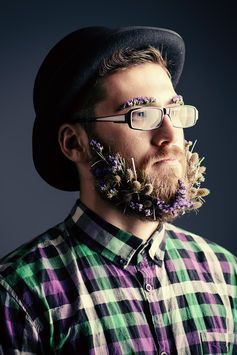

The subsequent media coverage, whether earnest or cheeky, drew attention to the establishment’s hirsute and tattooed proprietors, Gary and Alan Keery. Why were the bearded brothers subjected to such ire? Apparently because they’re hipsters.

It has become fashionable to hate the hipster. They are blamed not only for big issues such as gentrification, but also for the style crime of donning distinctly unhip fashions (at least in the eyes of other current or former subculturalists).

However, in this instance, many commentators rightly highlighted the fact that while hipsters and their quirky businesses - cafes that charge A$11 per bowl of cereal, for instance - are easy targets of scorn, they are only symptomatic of larger socio-economic realities and problems.

Following this story, I could not help but think what future cultural historians might make of the early twenty-first-century hipster.

Historicising youth subcultures

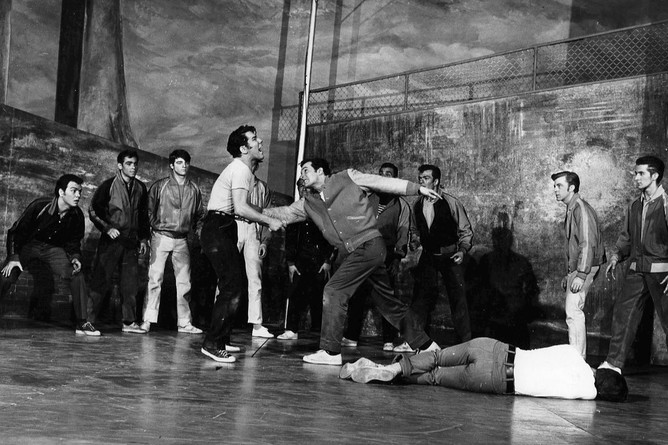

Over the last decade, in both popular media and scholarly work, there has been a surge of interest in the historicising of post-war youth subcultures. TV documentaries celebrating these narratives, such as the recent Street, Sound & Style (2015) and films like This is England (2006) and Northern Soul (2014), exemplify this growing trend.

On the academic front, the Interdisciplinary Network for the Study of Subculture, Popular Music and Social Change (currently based at the University of Reading) is made up of scholars from around the world who work on projects highlighting young people’s contributions to history. Many of these academics are interested in constructing narratives that attempt to make sense of why youth subcultures or lifestyles arose when they did.

Youth cultures characteristically embody the various sensibilities of an era. For instance, my own work on Mod culture depicts the original British subculture of the early 1960s as one that firmly wanted to put the trauma of war behind it by adopting all that was ultra-contemporary and up-to-the-minute. Instead of necessarily trying to reinvent neighbourhoods (though, to be fair, some Mods were also ambitious entrepreneurs), Mods focused on reconceptualising themselves.

The first iteration of the subculture saw male Mods cut dashing figures across London’s grey East End in their European-style suits and atop sleek, Italian scooters. For them, reaching for the “now,” the “new” meant looking beyond Britain’s shores.

The more commercialised, mid-sixties “Swinging London” version of the culture embraced pop art and space-age motifs. Female Mods wearing paper dresses or white and silver miniskirts jauntily reflected this forward-thinking.

Numerous authors have described the advent of punk in 1970s Britain, with its “no future” ethos, as a reaction to the economic crises of the decade. Recent ruminations on the 1980s New Romantics position them as make-up-laden yuppies - Thatcherites in disguise.

While it’s important to recognise nuance and variation within all youth subcultures or trends - and not paint any of them with one, totalising brush - it is also an intriguing exercise to consider how young people’s interests, sensibilities, and actions are symbolic of their times.

The hipster as a reaction to neoliberal values

Since reading about the London protests, I have thought about what future historians might make of the hipster. Attention has already been paid to the hipster as a possible manifestation of and/or reaction to the neoliberal values that have come to dominate contemporary life in the developed world. While some academics and cultural commentators have critiqued the hipster more generally, others also have discussed the group’s neoliberal sensibilities more specifically.

While some might see hipsters as “progressive”, this tag may be limited to their appearance alone. They are far from radical. Hipsters, as purveyors of pricey artisanal goods, are not trying to buck the system or advocate for social change. They are not “angry youth”.

If anything, their ardent embrace of entrepreneurialism and D-I-Y craftiness suggests that they have wholeheartedly accepted the fact that “the market” rules one’s lot in life. If living and thriving in hyper-expensive cities like London or New York requires opening a business that charges A$11 for a bowl of cereal, so be it.

Seemingly inherent to the hipster’s philosophy is the pragmatic acceptance that one’s possibilities are determined by the economic and political systems in place.

The fact that the hipster’s mode of operation has inspired such disdain - often among those who identify with more traditional youth subcultures such as punk - is likely because hipsters are seen as selling out (or buying in) rather than trying to resist or subvert mainstream realities.

While a full sleeve of tattoos may suggest more historically familiar notions of “rebellion”, the much-ridiculed Amish-style beard alludes instead to an austere, old-world sensibility. It is more than likely that many of those youths involved in the London protest would perceive hipster identity as the antithesis of their own.

In thinking through the existence of the hipster - and why he (see footnote) has become the target of such ire - it is important to ask ourselves this: Why is there still an underlying expectation that any seemingly “non-mainstream” group of young people are rebellious or want to “question the system”?

In a more pessimistic response to such a question, those who dislike the hipster may say that we have entered into an age where many young people are just happy to accept what is; that hipsters see themselves as living in a world that is both post-subculture and post-rebellion.

It is certainly easy to see how precarious employment, inflated costs of living, and heightened levels of surveillance would prompt capitulation on all fronts - making even the supposedly “hip” not quite what they seem.

A less damning and more supportive reading of the hipster would argue that young people do not have to “fight the power” or “system” because they are the system (and are reinventing it). The agency and empowerment offered to the millennials through their mastery of digital media has not only provided the world with Silicon Valley Wunderkinds, but hipster entrepreneurs, too. They are two functions of the same app.

While I am not the first to speculate on why the hipster has come to be a part of our contemporary world, I will certainly not be the last. What will the hipster come to symbolise about life in the early twenty-first century when historians of the future reflect on this era?

Note: Yes, “he”. The hipster is most always perceived as male, though there are certainly many millennial women who take part in this subculture or lifestyle (minus the Amish-style beards).

Christine Feldman-Barrett, Lecturer in Cultural Sociology, Griffith University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.