Orange-colored pigment in lichens may potentially cure cancer

A new study suggests that an orange pigment found in lichens, a plant-like organism made of fungi and algae, may possibly be used as an anti-cancer drug. The pigment is also present in rhubarb, a vegetable popularly used in pies, tarts and sauces.

Scientists at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University in Atlanta have discovered that the pigment, known as parietin or physcion, could slow the growth and kill human leukemia cells obtained directly from patients, without obvious toxicity to human blood cells.

The pigment could also inhibit the growth of human cancer cell lines derived from lung, head and neck tumors when grafted into mice, the team says in their study published in Nature Cell Biology.

The researchers, led by Dr Jing Chen, found the properties of parietin as they were looking for inhibitors for the metabolic enzyme 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, or 6PGD. Researchers have already found 6PGD enzyme activity increased in several types of cancer cells.

“This is part of the Warburg effect, the distortion of cancer cells' metabolism. We found that 6PGD is an important metabolic branch point in several types of cancer cells,” says Chen, a professor of hematology and medical oncology at Emory University School of Medicine and Winship Cancer Institute.

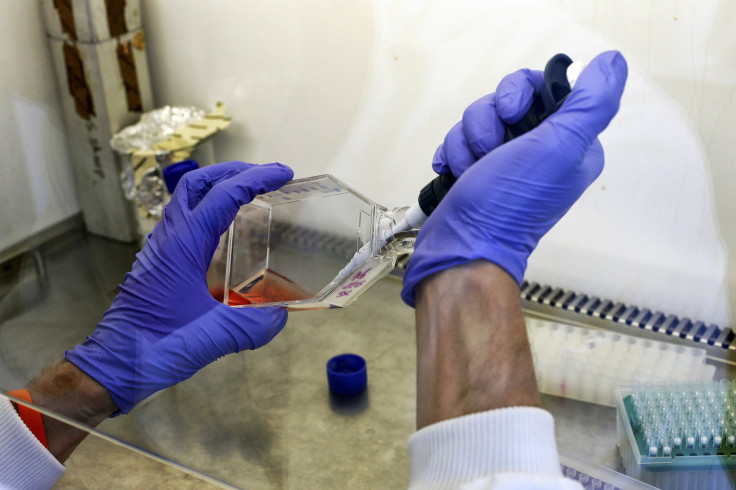

For the study, the team extracted the orange pigment from lichens to analyse its effects on cancer cells obtained from a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. They found that the doses of parietin could kill half the leukemia cells in culture within 48 hours. The team also discovered that the same doses left healthy blood cells unscathed.

Parietin is present in some natural food pigments, but has not been tested as a drug in humans, according to the team. While 6PGD inhibitors appear to be nontoxic to healthy cells, the authors note that more toxicology studies are needed to assess potential side effects and to see whether people with inherited conditions would be more sensitive to the drugs.

Earlier this month, scientists from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and the University of British Columbia in Canada have unexpectedly discovered that armed malaria proteins can kill cancer. According to the researchers, the combination of malaria protein and toxin seeks out the cancer cells, is absorbed, the toxin released inside, and then the cancer cells die. This process has been witnessed in cell cultures and in mice with cancer. After successfully testing this discovery in mice, the team hopes to be able to conduct tests on humans within four years.

Contact the writer at feedback@ibtimes.com.au or tell us what you think below.