People Who Stutter Experience Abnormal Brain Development As They Age, Study Finds

The study was conducted by researchers from the University of Alberta and was divided into two parts. The research included a total of 116 males aged between 6 and 48 years. Half of the participants stuttered while the other half didn’t. The second group was categorised as the controlled group.

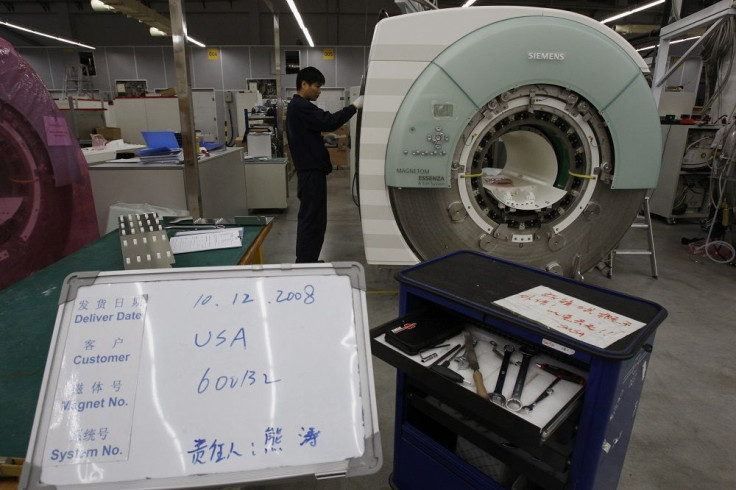

The first part included analysing MRI scans of the brain to check its development in children and adults who have a stuttering problem. The researchers noted abnormal development of grey matter in Broca's area, the region of the frontal lobe responsible for speech. It was the only abnormality found in the 30 regions of the brain the research team investigated.

"In every other region of the brain we studied, we saw a typical pattern of brain matter development. These findings implicate Broca's area as a crucial region associated with stuttering," said Deryk Beal, ISTAR executive director and an assistant professor in the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, in a press release.

As we age, there is a decline in the cortical thickness of the grey matter in our brains. This reflects how we become more efficient as we age. While researchers were able to observe a gradual but steady decline in the controlled group, no such observation was made in the brains of the people who stuttered.

"One interpretation of this finding could be that this area, in people who stutter, does not operate as efficiently within the brain network for speech production," Beal said. "It's like the chicken and the egg. We don't know if the changes we are seeing in this region of the brain are the result of a reaction in the brain to stuttered speech or some other difference in how the brain is operating elsewhere, or indeed if these changes are the cause of the disorder."

This is not the first study that looked into difference in the brain among those that stutter and those that don’t. In 2001, researchers from Tulane University addressed this topic with a study including individuals from both groups. They found that the right and left planum temporale was significantly larger with reduced interhemispheric size or more symmetry in the adults who stutter. They also noted that adults with perisitent developmental stuttering (PDS) had significantly more atypical anatomical features (average of 4 per individual) than controls (average one per individual). Some distinct features were seen in men versus women and right versus left handers. All of the right-handed women who stutter had extra-gyri but none had atypical planar asymmetry.

Findings of the current study were published online in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. The study was funded by the SickKids Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

To contact writer, email: sammygoodwin27@gmail.com