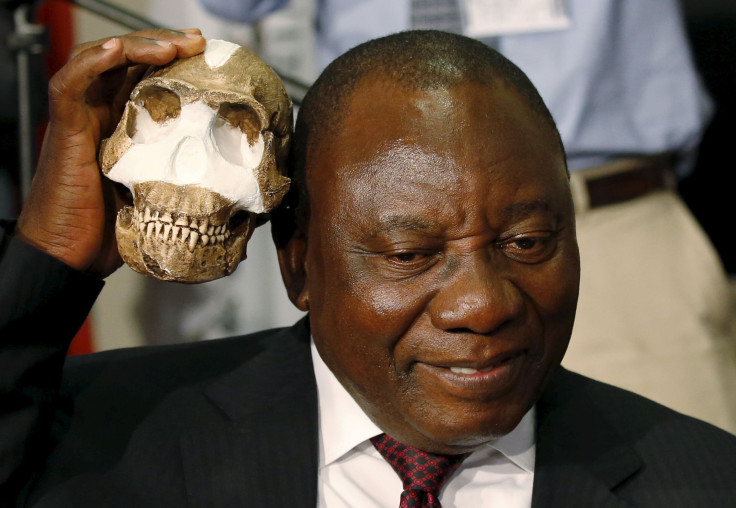

Scientists dig up new human-like species in South African cave

The way scientists think about the ancient ancestors of humans could change due to the discovery of new human-like species, researchers claim. An international team of scientists announced the discovery on Thursday of the human cousins, Homonaledi, in a burial chamber deep in a cave system in South Africa, believed to have the same ritual behaviour as modern humans.

The researchers, supported by the National Geographic Society and the National Research Foundation, unearthed 15 individuals representing the largest single discovery of its kind in Africa. The species, found in partial skeletons, has been named Homonaledi or naledi, which means “star,” referred on the name of the discovery site Rising Star Cave in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site in South Africa.

Naledi was classified a member of the group Homo, where humans belong, with its physical aspects resembling human hands and feet, but with curved fingers, the researchers said. The new species won’t be referred as the key to the missing link, but could be the “bridge” between humans and more primitive bipedal primates, according to Lee Berger, a National Geographic explorer-in-residence and research professor in the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa.

In the studies, published in the journal elife, the scientists were intrigued if the bodies, consisting of infants and adults, were placed in the cave intentionally. They believe that the species were placed in a burial chamber, which naledi people may have carried the individuals into the cave, and may be same ritual or repeated behaviour with modern humans.

"What we are seeing is more and more species of creatures that suggests that nature was experimenting with how to evolve humans, thus giving rise to several different types of human-like creatures originating in parallel in different parts of Africa. Only one line eventually survived to give rise to us," Professor Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum told BBC News.

However, the exact position of the naledi on the human family tree was still unknown, said Caley Orr, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Complicating the discovery is that the research team has not been able to determine the exact age of the species or the fossil site.

But they assume that naledi might have lived among the first of kind humans in Africa, about three million years ago. Naledi’s fossils were still "a very important discovery" that may help scientists understand the process of early evolution, Stringer said.

The discovery of the naledi that has a mix of modern and primitive features, according to Berger, would make scientists to rethink the definition of being categorised as a human, though he himself is hesitant to describe naledi as one. However, other researchers have claimed that the new species should be described as a primitive human.

But they added that current theories about humans should be re-evaluated, and that scientists have only just scratched human evolution’s rich and complex surface.

"The chamber has not given up all of its secrets," Berger said. "There are potentially hundreds if not thousands of remains of H. naledi still down there."

Contact the writer at feedback@ibtimes.com.au or tell us what you think below