Vital Signs: economy in a holding pattern

Vital Signs is a weekly economic wrap from UNSW economics professor and Harvard PhD Richard Holden (@profholden). Vital Signs aims to contextualise weekly economic events and cut through the noise of the data impacting global economies.

This week: Waiting, watching, and holding our breath.

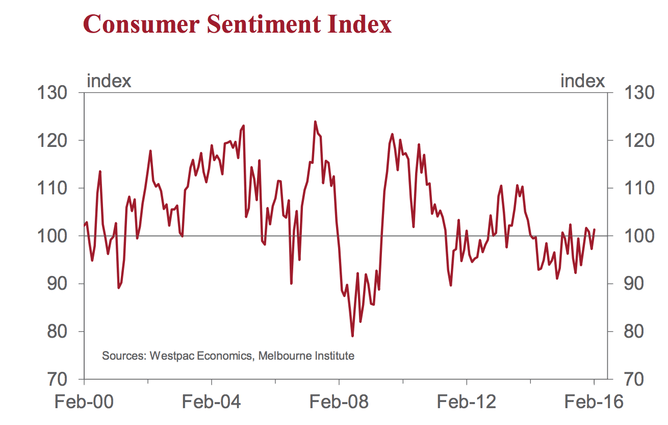

This week saw the release of a slew of economic indicators ranging from sentiment measures such as the Westpac-Melbourne Institute consumer confidence index and the NAB Business confidence index, to CBA quarterly profits and India’s GDP.

Business confidence was slightly down, while consumer confidence was markedly up – yet only back to the levels at the start of the year. Optimists barely outnumber pessimists and, tellingly, the housing index is 21% below where it was a year ago. Worse still, most of the boost is from lower petrol prices which, though good for households in the short-term, actually reflect global growth concerns at present.

Job ads growth turned positive, but only just. The Australian labour market isn’t weak, but it isn’t super strong, either. Taken together with the NAB business confidence numbers it reflects businesses that are waiting and seeing before investing and expanding.

At the macro and international level, India’s fourth quarter GDP growth came in at an annualised rate of 7.3%, down from 7.7%. Worse, still, there were concerns about the voracity of the official numbers. And although India’s growth outpaced China’s 6.8% annual rate, those looking for a new engine for the global economy did not find much solace in the Indian numbers.

Janet Yellen certainly wasn’t summarising Australian data when she testified before the Financial Services Committee of the United States Congress. But she might as well have been when she said “Financial conditions in the United States have recently become less supportive of growth”. That hearing also highlighted the fact that investors continue their flight to quality – making safe assets like US Treasuries and certain other sovereign bonds in such high demand that interest rates are sometimes negative. That same flight to quality is, in the US, making it increasingly expensive and difficult for lower-quality borrowers to obtain credit.

That exact phenomenon – a rise in the cost of credit for lower-quality borrowers – is a key thing to watch in Australia. If that happens here then we can expect the cost of mortgages to increase for certain borrowers who can least afford it. That is historically one way that housing bubbles burst. Not that I’m say we having a housing bubble in Sydney and Melbourne, but just suppose…

Oh, and if all this economic news wasn’t depressing enough, there’s currently nearly one chance in four that either Donald Trump or Bernie Sanders will be elected President of the United States.

As with the US primaries so it is with the Australian and global economy. We will have to wait and see. Nervously.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.