The world economy can benefit from a vindicated Trump

Vital Signs is a regular economic wrap from UNSW economics professor and Harvard PhD Richard Holden (@profholden). Vital Signs aims to contextualise weekly economic events and cut through the noise of the data affecting global economies.

This week: China’s growth continues to slow, US inflation remains stubbornly low, Australian interest rates may not prove as predictable as everyone thinks, and Xi Jinping speaks sense on trade.

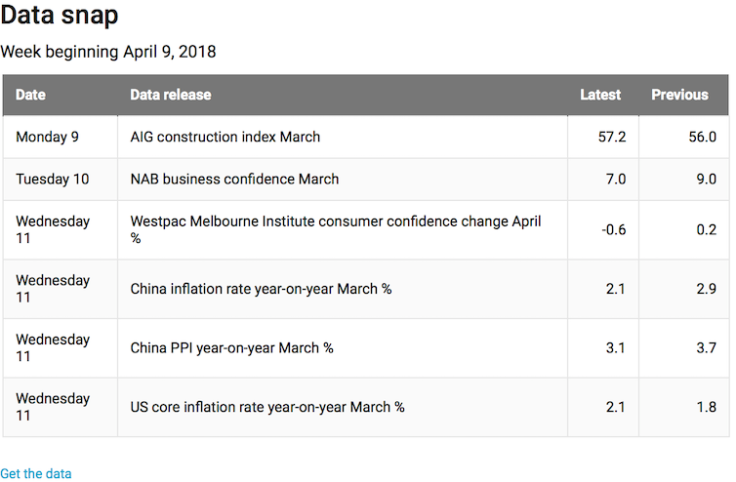

I am in Beijing this week, so I will start with important Chinese data. The producer price index (PPI) grew at 3.1% for the 12 months to March, down from 3.7% for the 12 months to February, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics. On the consumer side, the CPI grew at 2.1% on the previous year, compared to February’s 2.9% figure, and well below market expectations of 2.6%.

All of this seems to reflect a gradual slowdown in the pace of economic growth in China. But it is consistent with the general slowdown that happens after a three decade run of breakneck growth, and also efforts to tighten credit in light of concerns about financial stability.

In the US, consumer prices actually fell 0.1% in March. But given the previous year’s equivalent month rolling off, this left the CPI up 2.4% for the last 12 months. Core CPI, which strips out the most volatile components of the index, was up 2.1% for the last 12 months.

The Federal Reserve focuses on a different measure of consumer prices – the Personal Consumption Expenditures index (PCE). This arguably takes better account of energy and food expenditures. It is still below the Fed’s target of 2%. In the minutes of the last FOMC meeting, the Fed observed:

The projection for inflation over the medium term was revised up a bit, reflecting the slightly tighter resource utilization in the new forecast. The rates of both total and core PCE price inflation were projected to be faster in 2018 than in 2017. The staff projected that inflation would reach the Committee’s 2 percent objective in 2019.

In other words, nobody understands why, with unemployment so low and the economy growing at a reasonable clip, inflation remains so low. It is one of the key economic puzzles of the past decade across all advanced economies.

This week saw two notable Australian confidence indices report for the month. The NAB business confidence index dropped 2 index points this month to +7. This sits just above the medium-run average of +6. It’s dangerous to speculate about month-to-month movements – particularly of a survey (as opposed to revealed-preference data) – but the Trump trade war looks like a plausible culprit.

On the consumer side, the Westpac-Melbourne Institute consumer sentiment index was down 0.6 points in April to 102.4. That’s still up 3.4 points for the past 12 months, although 100 is the break-even between optimists and pessimists, so it doesn’t reflect overwhelming consumer confidence. Digging into the details of the “family finances” sub-index, it appears concerns about slow wage growth and high household debt are a drag on confidence. Sounds about right, doesn’t it?

The Australian Industry Group’s Performance of Construction Index (PCI) was up 1.2 points in March to 57.2. The break-even for this index is 50 index points, so 57.2 represents fairly significant expansion. This was driven largely by commercial, as opposed to residential, construction.

Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe made some wide-ranging remarks in a speech to the Australia-Israel Chamber of Commerce in Perth on Wednesday. Setting aside the avalanche of uninspiring charts that have become customary padding in such speeches, he said two things of note: one about wages and one about interest rates.

Regarding the persistently low wage growth in Australia, he said:

…we expect a further pickup in the Australian economy. Increased investment and hiring, as well as a lift in exports, should see stronger GDP growth this year and next. The better labour market should lead to a pickup in wages growth. Inflation is also expected to gradually pick up. So, we are making progress.

“We are making progress”? All the statements that preceded that conclusion were about what the governor expects to happen, not what is happening. So my conclusion would be “we are hoping for progress”. I hope the governor is right about how the economy will evolve, but at this point it is far from a sure thing. It can’t be dialled in with scientific precision, so requires a leap of faith. A little more Kierkegaard than Einstein.

On interest rates, Lowe said:

…it is more likely that the next move in the cash rate will be up, not down, reflecting the improvement in the economy. The last increase in the cash rate was more than seven years ago, so an increase will come as a shock to some people. But it is worth remembering that the most likely scenario in which interest rates are increasing is one in which the economy is strengthening and income growth is also picking up.

He’s certainly right to continue to warn massively over-leveraged Australian households that their mortgage payments could go up. But, again, his optimism about that happening along with rising incomes seems rather misplaced. Moreover, will the next move on official rates really be up? There’s a very plausible scenario that the macro economy continues to disappoint and the RBA gets caught needing to cut rates. It might not happen, but it’s not exactly beyond the realm of possibility.

Trump trade war update

There were interesting developments in the tit-for-tat tariff announcements between the US and China this week. Speaking at the Boao Forum for Asia conference in Hainan, Chinese President Xi Jinping appeared to attempt to deescalate tensions with the Trump administration.

Xi spoke of further opening up of the Chinese economy, including reducing tariffs on car imports (currently 25%) and providing stronger intellectual property protections (long a cause of consternation for multiple US administrations). But in perhaps the clearest signal of trying to cool tensions with President Trump, he said: “We must restrain from beggar thy neighbour policies”.

The happy case here is that Trump gets the message, doesn’t overreach, and stops threatening further US tariffs. That’s right, the best we can hope for is a smug President Trump, who feels vindicated despite being an economic vandal.

Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.