Young Australians missing out on jobs to older workers and migrants: study

Young people have missed out at the expense older workers and migrants in the job market, according to new research on youth employment. Government policy and Australia’s sluggish economy have added to the problem.

While Australia avoided the worst of the global financial crisis, unemployment among its youth has mirrored many countries who went into recession.

Prior to the crisis, youth unemployment in Australia was 8.8%, close to the low rates of the 1970s. By 2015, it was 13.9%. While prime-age workers, those aged between 25 and 54 make up a greater proportion of the labour force, the crisis had a greater impact upon young people.

In response, attempts to address youth unemployment have either attacked young people through a restriction of unemployment benefits or have been completely lacking from government policy agendas. The Coalition government introduced a “youth employment strategy” a part of the 2015 budget, which included the “Youth Work Transition” program for those “at risk of long term welfare dependence”.

Our research published in the latest volume of the Journal of Applied Youth Studies suggests the policy levers aimed at population ageing may have been detrimental to youth engagement in the labour force, in recent history at least. Increasing female and mature labour force participation and increasing immigration, combined with a lack of employment demand post the financial crisis are all influencing factors.

Gen Y stay on learning while boomers and migrants continue earning

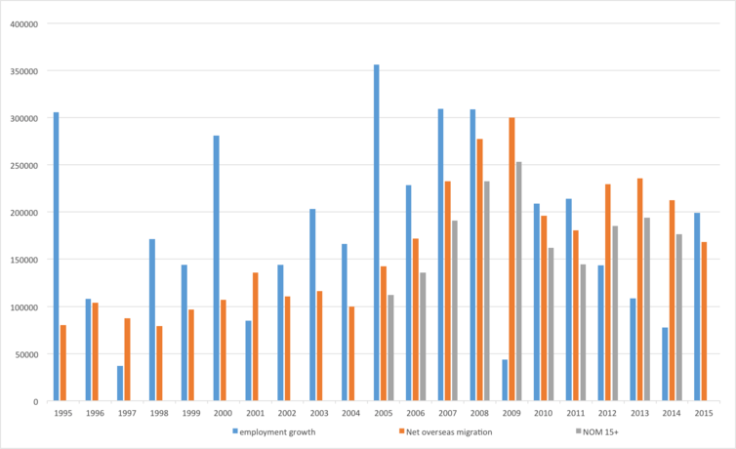

Participation in the labour force and subsequent employment is influenced by the demand for employment. Over the past two decades, the rate of employment growth generally exceeded the rate of growth in the size of the labour force (the supply of labour) for most of the period, resulting in increases in the employment to population ratio. In 2009, however, there was a decline in both the employment growth rate and the size of the labour force, which was caused by the economic downturn resulting from the financial crisis as well as some effects resulting from the ageing population.

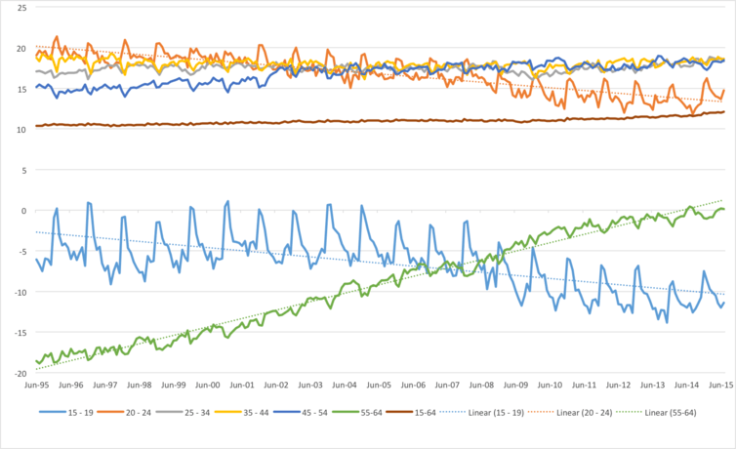

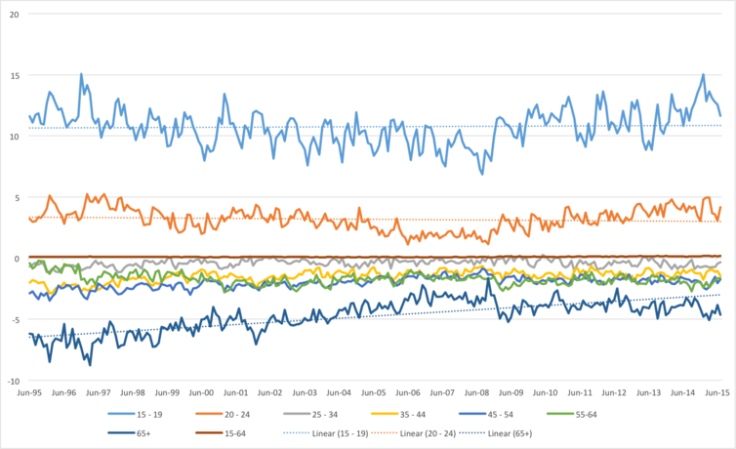

The greatest change in labour force participation rates over the last 20 years has occurred among the youngest and oldest segments of the Australian working age population. Participation rates have changed markedly for youth (aged 15 to 24) and those aged 55 to 64. The deterioration in participation for young people is reflective of their increased participation in education and training as well as the relative level of confidence the group has in securing work.

The dramatic improvement of participation among 55 to 64 year-olds has completely closed the gap between the age specific rate and the overall participation rate. This is consistent with policy intervention to increase both female and mature age labour force participation rates. The raising of the superannuation preservation age and aged pension age (for women), has also played a role. The impact of the financial crisis on the value of superannuation investments has also prolonged the planned exit from the labour force by older workers.

The youth unemployment rate, derived from the labour force participation rate, has been consistently greater than the overall unemployment rate while all other age groups have averaged lower. However, since the financial crisis, youth unemployment has not recovered at the same rate as for older age groups.

Also, the 55-64 group of workers has increased considerably in size, while the youth group only marginally over the last two decades. The 45-54 group is also growing. And it’s happening as labour force participation levels increase and the employment market languishes. When combined, these factors mean youth employment may deteriorate further.

This predicament has been exacerbated by the introduction of the demand driven skilled migration program since 2008. The shift highlighted a significant and growing mismatch between the skills and experience on offer and those demanded by the Australian labour market. As Figure 3 illustrates, the impact of this policy focus is clear. Since 2005, overall employment growth has exceeded total net overseas migration (NOM), providing some justification for the introduction of the employer-led immigration policy.

But since its introduction and the subsequent financial crisis, net overseas migration has considerably exceeded employment growth. The labour market is now far larger than employment demand. In the five years to 2015, net overseas migration exceeded employment growth by more than 30,000.

The importance of youth policy

In short, young people have missed out at the expense older workers and migrants, which reflects the current policy settings in place. As we have stated before, young people have been omitted from the Intergenerational Reports.

Youth policy in Australia has become synonymous with education and training policy, overly focused on young people making a series of linear transitions from schooling to post-school qualifications and finally to the full time labour market. This is in spite of decades of research which has demonstrated that transitions for young people in the contemporary labour market are anything but linear.

Efforts to address youth unemployment have focused on skill deficiencies, work ethic and the education system producing job-ready workers. The reality is that poor economic performance and high levels of skilled migration are standing in the way of young Australians entering the labour market for the first time.

We know that once a person reaches 25 they’re more likely to be in the workforce. This suggests that the initial transition from school to work is failing young people. There’s also a reluctance on the part of employers to engage and invest in young people with training. To address this, governments need to put youth at the forefront of policy making.

Lisa Denny, Demographer/PhD Candidate, University of Tasmania and Brendan Churchill, Research Fellow, University of Tasmania

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.