HBO Series Tackles Spain Taboo Over Basque ETA Separatists

Ten years after the separatist group ETA renounced its armed struggle, few will speak of the bloody campaign that ravaged Spain's Basque country, but a new TV series is hoping to shatter that taboo.

With the conflict still an open wound, HBO's "Patria" -- a highly anticipated adaptation of a novel of the same name by Spanish writer Fernando Aramburu -- hits the small screen on Sunday in Spain and across the Americas.

"The wound, because it is so deep, will take time to heal. The Basque Country has not forgotten ETA," says Gorka Landaburu, a Basque journalist who lost several fingers and an eye when he opened a letter bomb sent by the group.

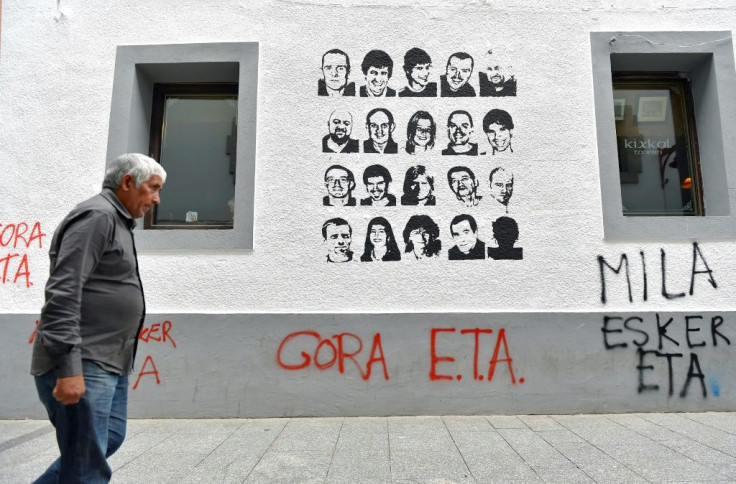

ETA's symbol -- a snake wrapped around the handle of an axe -- is no longer seen on the walls of villages in the region, but at a bend on one mountain road, a scrawl of graffiti demands the release of a Basque militant while another calls for "a full amnesty".

But across the region, a conspiracy of silence enshrouds the memories with few prepared to open up about a bloody and painful era that many would prefer to forget.

"There is a taboo," says Ana Aizpiri, whose brother Sebastian died two ETA bullets to the back of the head in 1988, "a blanket of silence that extends even to the dining table".

"No-one mentions that empty chair," she said.

But Sunday's pilot episode of "Patria" is hoping to shatter that silence with a televised version of a novel about the families whose lives were shattered by the violence of ETA.

"It is a very sensitive subject, the wounds remain open and we still have not managed to digest" the years of terror, Aitor Gabilondo, screenwriter and executive producer of "Patria", told AFP after a screening of the eight-part series at the San Sebastian film festival.

For 40 years, the bloody violence engulfed the Basque Country, a region which is home to just 2.2 million people.

Formed in 1959 by a group of frustrated nationalist students, ETA waged a decades-long campaign for Basque independence in northern Spain and southwestern France that killed an estimated 853 people.

But its attacks were countered by violence from far-right groups and shadowy death squads such as the state-sponsored Anti-terrorist Liberation Groups (GAL) -- which emerged in the 1980s -- that between them killed dozens of ETA militants.

After declaring a permanent ceasefire in 2011, ETA began surrendering weapons in 2017 before disbanding completely in May 2018.

"Terrorism, violence and blackmail may have disappeared but there are still scars that need to be healed. It will be a long process before we can live together," says Landaburu.

The idea of coexistence is one that sticks in the throats of many here.

"In the Basque Country, we used terrorism against each other," reflects Eduardo Mateo Santamaria of the Fernando Buesa Foundation for peace.

"Those who fired the gun, who placed the bombs are your neighbours living opposite, your family, your own people."

Ane Muguruza, whose father Josu was a lawmaker for ETA's political wing who was murdered in 1989 by far-right militants, also wants to be recognised as a victim.

"They killed my father seven days before I was born and my mother was tortured. My family has suffered state violence in its very flesh," says the 30-year-old.

"How can we say we're at peace when the state continues taking revenge on ETA," she asks, pointing to Madrid's policy of keeping ETA prisoners locked up far from the Basque Country.

For the past 18 years, Xochitl Karasatorre has only ever seen her father, a former ETA militant, inside the visitors' room at a prison in France.

"It is very complicated to talk about reconciliation when one side has not made any steps towards the other, " says Joseba Azkarraga of Sare which lobbies on behalf of the prisoners.

A peace activist for nearly 25 years, Edorta Martinez is hoping the younger generation will end the unspoken oath of silence.

"The young people, those 25 and under, are totally ignorant of what happened. They ask questions but these are conversations you have in private," he told AFP.

"We must not make the same mistake as with the civil war (1936-1939)," said Martinez of the years in which the violence of the conflict and the ensuing dictatorship was not openly discussed for fear of provoking a spiral of score-settling.

"We must not wait 70 years before looking back."