Microfibre shed from spandex or fleece apparel imperils marine life

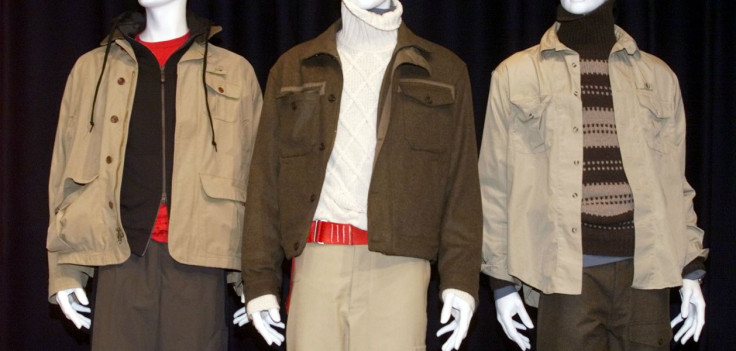

Washing a single polyester jacket or spandex yoga pants can send tiny synthetic microfibres into waterways, where they can absorb toxins and get eaten by marine species. The invisible nightmare, coming out from many households' washing machines, was uncovered by a study made by environmental experts from Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California, Santa Barbara.

The study was conducted by a team of researchers in the United States that included environmental scientist Niko Hartline and Patagonia environmental research associate Stephanie Karba. Among the findings was that synthetic jackets release about 1.7 grammes from the washing machine after laundering. The complete report was recently published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Microfibre masses

In essence, microfibre masses were recovered from conventional machine washing of new or old garments made of synthetic textiles. Polyester, acrylic, nylon are petroleum-based plastics spun into very tiny threads to comprise typical fabrics people wear. When laundered in washing machines, the clothing pieces release microfibre particles that eventually end up in oceans.

Environmental experts opine that microfibre is even more abundant in lakes and rivers than microbeads in some shampoos and body wash. Wool apparel and cotton clothing shed fibers, too, but those materials biodegrade.

It can be noted that in 2011, a similar study entitled "Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Woldwide," was conducted by researchers from Ireland, Australia, Canada and United Kingdom. They found that a large quantity of microplastic fibres found in the marine environment emanate from sewage as a consequence of washing of clothes.

As people use more synthetic textiles, contamination of habitats and animals by microplastic was foreseen to increase back then. Now it has become an alarming reality.

What industry and consumers can do about it

Mitigation measures to lessen the release of microfibre into the environment after laundering may be done with the cooperation of apparel manufacturers, but it will entail substantial changes. Responsible clothes manufacturers would have to conduct their own analyses of their product lines to assess how they are contributing to microsynthetic fibre pollution. Policy makers, consumers and waste managers may also contribute their share to lessen the negative environmental impact.

The bottom line is that the shedding of microfibre in the wash can be limited. Wastewater treatment plants upgrading was not deemed a feasible way to curb microfiber pollution.

In any case, people can exert greater vigilance to help keep microfibre out of the ocean. The study findings may prompt customers to realise the importance of opting for high quality garments, instead of settling for clothes that shed during the laundering process.