Research Finds That Family Income Affects Children's Brain Development

A recent US study suggests that children who belong in families with lower incomes are likely to experience slow brain development. The study further recommends that programmes that aim to alleviate poverty may have significant effects in the overall cognition and functionality of children.

It has been suggested several times that socioeconomic factors play an important role in the cognitive performance of children; but it is only now that the study published in Nature Neuroscience has tackled the effects of socioeconomic status to anatomical brain development.

The research involved more than 1,000 children aged between three and 20. It was conducted through cognitive examinations, brain imaging, DNA testing and parental survey of education of income.

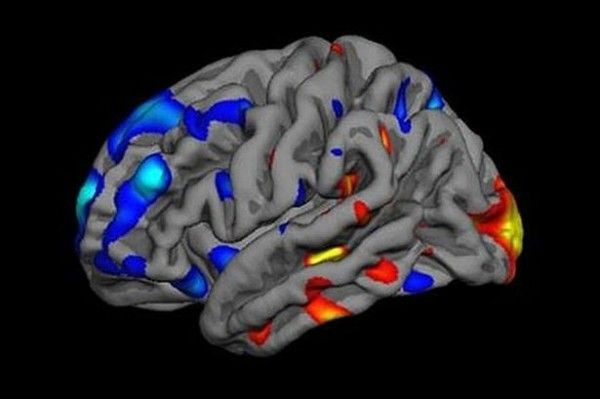

The study centralised on the investigation of two key socioeconomic factors, which include parental education and family income, including their effects on the development of the brain’s surface area and cortical thickness. As these anatomical structures are linked to human intelligence, the researchers focused on these areas. The researchers revealed that more intelligent children have thinner cortices at the age 10, and this continues on through adolescents. Conversely, the brain’s surface area are thicker amongst these same children.

Further into the study, the researchers found that both parental education and family income impact brain development; however, it is the latter that has shown the more significant relevance to the investigation. Co-author Associate Professor Kimblerly Noble of Colombia University in New York says that children belonging to low-income families have exhibited more relationship between their socioeconomic status and the development of the brain surface area.

There seems to be a direct correlation between each dollar earned in the family and the increase in the brain surface area of children in the low income class. Noble says, "Dollar for dollar, we see a greater increase in surface area among the most disadvantaged children."

The effect of socioeconomic status to brain development is specifically noted in the areas of the brain regulating language, memory, and problem solving functions. The researchers, however, iterate that further investigation is warranted to further support the findings of the study.

According to the research team, the results may implicate that higher-income families can provide more nutritious food, more conducive learning environment, safer neighbourhoods, and lesser exposure to pollutants and stress for their children. However, they iterate that these suggestions do not, in any way, imply that socioeconomic status cannot change the way these kids’ brains develop. There are numerous factors associated with brain morphometry; school and home interventions greatly impact the cognitive and behavioural aspects of children, particularly those in the low-income class.

Another investigation is yet to be initiated, as Noble says her team is currently talking with a group of social scientists to explore on their findings. This new research aims to discover ways on how the study can benefit children in the low-income scale. "We are proposing to recruit a national sample of low-income mothers, randomise half to receive a large monthly payment and half to receive a modest monthly payment, and assess the causal impact of this income supplementation on children's cognitive and brain development. If evidence supports our hypotheses, then it would suggest that governments would be well served to increase the generosity of social services for the most disadvantaged families," Noble closes.

To contact the writer, email rinadoctor00@gmail.com