Tinkering with genes can help make intelligent babies

A new facet has been added to the ongoing debate on ethics of genetic engineering with scientists exploring the link between genes and intelligence. The study is currently under attack for its racial undertones and the researchers are being urged to consider the ethical aspects associated with such a study.

Researchers should "consider the limits we should place or steps we can take to be sure we don't repeat historical errors such as forced sterilisation of the “feeble-minded” in the early 20th century," says Mildred Solomon, president of the Hastings Centre in New York, according to the National Geographic. The Centre had, in early December, hosted an event for scholars and ethicists to discuss the future of intelligence research.

The bioethicists at Hastings Centre became interested in the subject last year when a behavioural geneticist approached the Johns Hopkins Centre for Talented Youth for permission to study its alumni who had been identified in their teens as “highly gifted” based on their SAT scores. The John Hopkins centre approached Hastings Centre for advice.

Despite a growing body of scientists opposed to genetic editing on ethical grounds, National Geographic says it may already be too late to stop such research. According to National Geographic, twin studies conducted in the early 1970s have already shown that identical twins (who generally share 100% of their genes) are more similar in terms of general intelligence than fraternal twins (who share around 50% of their genes).

Erik Parens, research scholar at Hastings, construes this to mean that general intelligence does have a genetic component. General intelligence which relates to the ability of a person to reason, plan, solve problems, comprehend ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience,

However, scientists believe it is not one but many genes that influence intelligence and hence finding the connection is a challenging task.

Robert Plomin of University College, London, told BBC Radio in a recent interview that the ultimate test would be to find the genes that affect the heritability of learning ability. “We're talking about many, many genes, thousands perhaps, of very small effects,” he said, expressing unhappiness with those who do not want such research to continue.

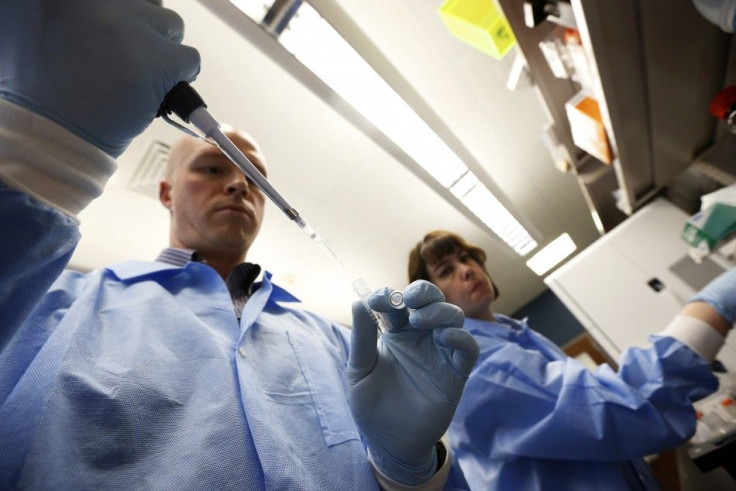

Meanwhile, Professor Cecile Janssens of the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University says that genome editing technology called CRISPR-CAS9 may not help in altering complex human traits such as intelligence, reports Tech Times.

Janssens further says that the technology only allows inexpensive and accurate modification of human DNA in relation to biomedical research. Scientists need to take into account what can and cannot be genetically edited in human DNA.

Contact the writer at feedback@ibtimes.com.au or tell us what you think below.