Coup Shatters Myanmar Military's Dalliance With Democracy

This week's coup in Myanmar risks resurrecting the troubled nation's international pariah status and destroys a civilian power-sharing agreement where the generals still maintained huge control, leaving many wondering why the military took such a drastic step now.

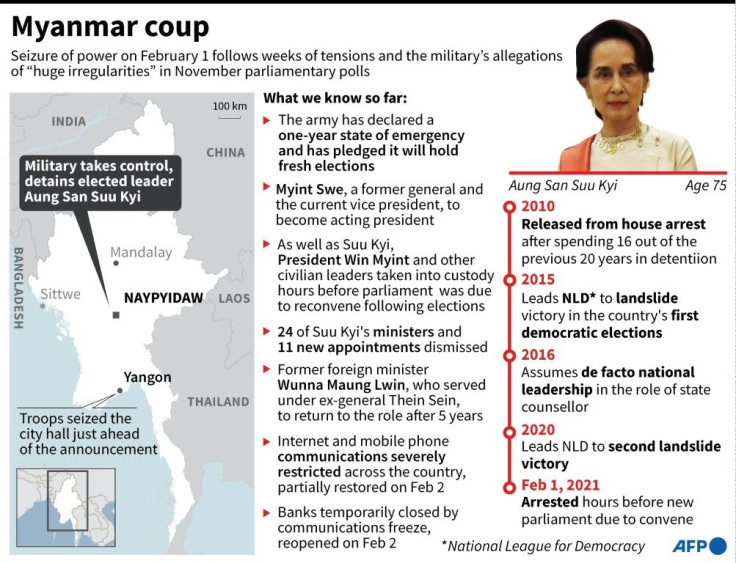

The sight of soldiers with rifles back on the streets of Naypyidaw -- and democracy advocate Aung San Suu Kyi spirited back into detention -- has conjured up memories of Myanmar's darkest days during 49 years of junta rule.

After a 10-year experiment with moving towards a more democratic system, the generals are back in charge, sparking a chorus of international condemnation and the threat of renewed sanctions.

The military justified its coup by alleging last November's elections were fraudulent.

Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) party won an even bigger landslide than when it swept to power in 2015 -- while the army's own parties received an embarrassing drubbing.

But in Myanmar a stunning electoral mandate does not mean full power to govern.

Under the country's junta-scripted charter, the generals still operate key levers of power.

A quarter of parliamentary seats are reserved for the military -- guaranteeing it a veto on any changes to the constitution. Key ministries such as interior and defence stayed in their control while lucrative military-owned conglomerates remained a core part of the economy.

"It was always an uneasy relationship and a hybrid regime -- not quite autocratic and not quite democratic," Herve Lemahieu, an expert on Myanmar at Australia's Lowy Institute, told AFP.

"It's collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions."

So why would the generals throw away an already favourable system?

At the centre of the coup is Min Aung Hlaing, the mercurial head of Myanmar's armed forces.

Suu Kyi, who was locked up for years by the junta, trod carefully around figures like Min Aung Hlaing to avoid giving them any pretext to launch a coup as she tried to reform a sclerotic country devastated by years of junta rule.

She even passionately defended the military's sweeping crackdown against Myanmar's Muslim Rohingya population, a stance that hugely tarnished her international image as a democracy icon.

But analysts say the relationship between Suu Kyi and the top brass had in fact been deteriorating.

"It really soured in the last year," Min Zaw Oo, executive director of the Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security, told AFP.

Civilian leaders, he added, may have underestimated the military's allegations of election fraud and their determination to challenge the results.

"There was no proper dialogue... they didn't take it seriously," he added. "I think that was an insult... there's a lot of pride issues."

Myanmar's military is no monolith. Some factions were open to reform and instrumental in creating the quasi-democratic agreement that brought Suu Kyi to power.

But there have long been question marks over whether more conservative generals were ever really committed to democracy.

Speculation is rife that Min Aung Hlaing may have decided to act as time ticked down on his military career.

He was due to retire in the summer and had previously hinted at future plans to run as a civilian politician.

But the embarrassing performance of the army-linked USDP party signalled little hope of overturning Suu Kyi's star power with the electorate.

"The thundering NLD victory at November's election seems to have brought simmering civilian-military tensions to a head and convinced Min Aung Hlaing and the (army) high command that the constitution is no longer a sufficient bulwark," Sebastian Strangio, an expert and author on Southeast Asia's politics, told AFP.

Generals such as Min Aung Hlaing have already been sanctioned by the US for their role in the Rohingya onslaught.

Condemnation from Western leaders were immediate, and even China called for all sides to "resolve differences".

But "I don't think risking international opprobrium is of any concern to the military top brass," Renaud Egreteau, a Myanmar expert at the City University of Hong Kong, told AFP.

The coup is not without risks, even for an organisation with decades of experience in repressing its own people.

The generals now inherit full control of a deeply troubled nation. The economy has been ravaged by the pandemic and vast swathes of its electorate have been disenfranchised.

As Myanmar analyst David Mathieson put it: "The military has essentially picked a fight with the whole country."