Labor's pay policy merely hints at helping low paid workers rather than actually doing it

There is little dispute the pay packages for leading chief executives have reached gross and excessive proportions while the wages of poorly paid Australians have stagnated.

Pay ratios - a measure of disparity between the highest and median (representative) wages within a company - stand at around 100:1 in Australia’s largest firms. That’s up from 15:1 in the late 1970s.

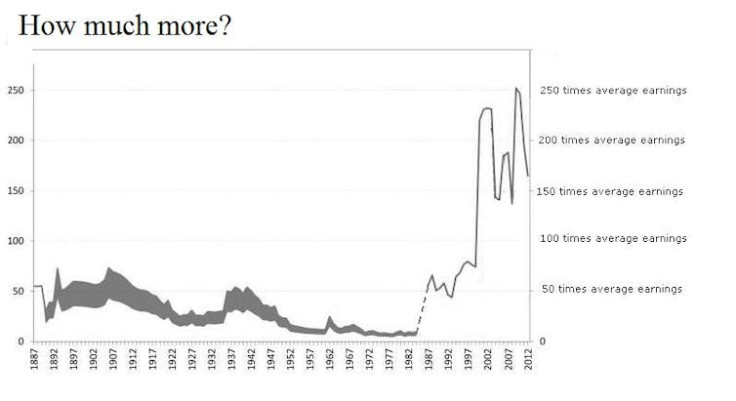

This graph, from a study prepared by Labor assistant treasury spokesman Andrew Leigh and Melbourne University economist Mike Pottenger in 2013, shows the pay packet of BHP’s chief peaked at around 50 times average earnings in the early 1900s and then slid to just 10 times average earnings in the 1970s before soaring again to well over 100.

Last week Leigh announced Labor’s response. In government Labor would require stock exchange listed firms with more than 250 employees to report the ratio of their chief executive’s pay to that of the median worker.

It is an idea adopted in the United States and in Britain, where it has been championed by Conservative Prime Minister Teresa May.

But a study of mine in the August edition of the Journal of Australian Political Economy finds no evidence such reports lift the pay of low or middle-ranking workers.

Reporting needn’t lift pay

Where reporting is not backed by laws requiring an increase in workers’ pay – and Labor’s present proposal isn’t - they simply encourage shareholders to take their chief executive’s pay and hand it to themselves.

My study found even where shareholders have voted to cut their chief executive’s remuneration (in some cases by as much as 32%) the funds freed have been passed on to shareholders rather than workers.

Numerous studies since the early 2000s have found about 60% of Australian shares and liquid wealth are held by the wealthiest 10% of Australians.

Accordingly, the only likely redistributive effect of pay disclosure laws of the type proposed by Labor will be to redistribute wealth among the already wealthy.

Pay disclosure laws can certainly serve an educative purpose by making public the size of shameful disparities. But as some British trade unionists have asked, “how do you shame people who are shameless?”.

In some form or other Australia, the US and Britain have already had pay disclosure laws for nearly a decade.

It’s an old idea

Australia’s Corporations Act requires listed companies to annually disclose the complete remuneration packages of all their directors and their five most highly paid executives. It gives shareholders the right to reject excessive remuneration packages.

Since the introduction of the provision in Australia, total chief executive pay has increased rather than fallen.

Other countries impose requirements

There are a number of measures Labor could take that would actually redistribute executive pay to lower paid workers.

One, proposed by UK Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn and leading economist Anthony Atkinson would cap executive pay at 20 times the wage of a firm’s lowest paid worker and require equal pay for equal work.

It’s an idea Labor in Australia ruled-out on the ground that a scheme in the US that capped executive pay at US$1 million per annum failed because companies rewarded executives instead with stock options and bonuses.

But as the UK think tank the High Pay Centre points out, that could readily be curbed simply by requiring companies to include all forms of remuneration (not just salary) in the calculation of the executive-to-worker pay ratio.

In countries such as in Spain and Germany workers are given an enforceable vote on what they perceive to be a fair ratio between CEO and worker pay. Where this practise exists at the Mondragon Corporation in Spain, the ratio between executive and worker pay is no higher than 9:1.

Other measures include a pay ratio tax of the kind in force in Portland Oregon which imposes a 10% tax on the profits of companies whose pay ratios exceed 100:1 and the so-called Buffett rule proposed in the US which would impose a minimum 35% tax on incomes of more than US$300,000.

Another mechanism is compulsory company-wide profit-sharing of the kind that is required in French companies with more than 50 employees.

Australia could too, if it wanted

As Australian Labor’s announcement made clear, its new policy comes not from UK Labour or from innovative ideas being tried elsewhere, but from the policy handbook of the British Conservative government and Prime Minister Theresa May.

Overseas and Australian experience suggests that without specific action to redistribute executive pay, Labor’s policy will achieve little, merely suggesting redistribution instead of achieving it.

Eugene Schofield-Georgeson, Lecturer, UTS Law School, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.