New poll shows British people have become more positive about immigration

Michael Gove, the British environment secretary, sparked a heated debate when he said recently: “Britain has the most liberal attitude towards migration of any European country. And that followed the Brexit vote.”

His implication that the Brexit vote was a force for a more positive view of immigration in Britain has been vigorously challenged by some.

And you can see why it might grate: analysis by King’s College London shows that media coverage of immigration tripled in the campaign, and was “overwhelmingly negative”.

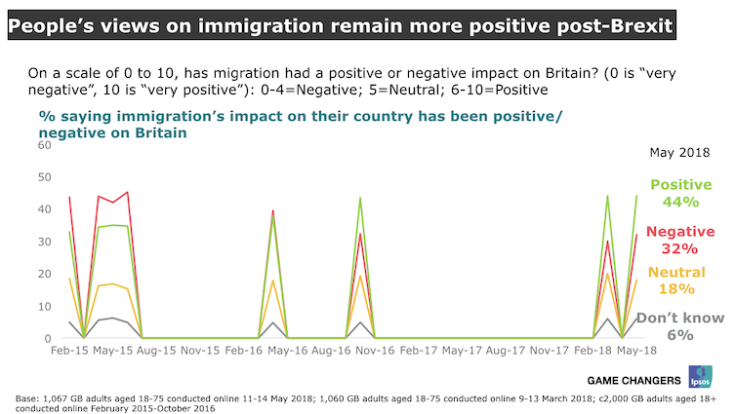

But Gove is right to say that people in Britain are now more positive about immigration, as shown by new polling released by Ipsos MORI, tracking attitudes towards immigration after the recent Windrush scandal.

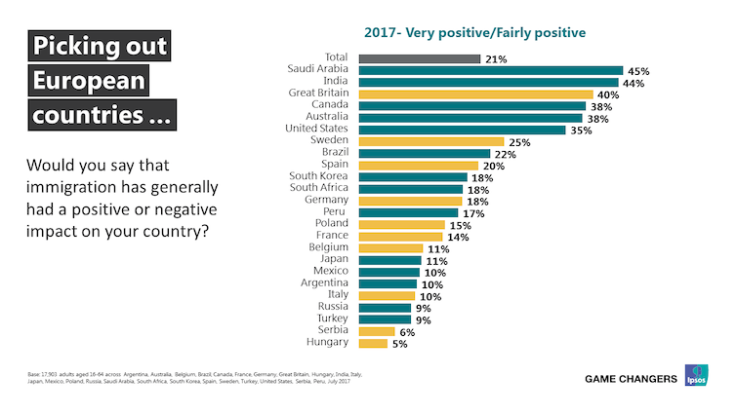

Gove cited an Ipsos survey from the end of 2017, which does indeed show that from the ten European countries included, Britain is most likely to think immigration has had a positive effect on the country.

A more recent European Commission survey across all 28 EU countries shows that, while the UK is not quite top, it is the third most likely to say that immigration is an opportunity rather than a problem, behind only Sweden and Ireland.

And this is a shift that can’t be explained purely by the weight of negative media coverage of immigration dying down after the referendum. I’ve been reviewing immigration attitudes for nearly 20 years, and I’m really not used to seeing Britain at the top of any league table of immigration positivity: this is something new.

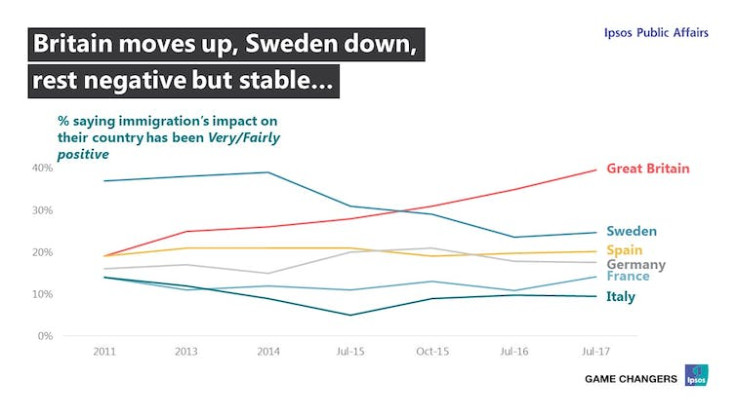

As the chart below shows, positive attitudes have doubled in Britain since 2011, while they’ve flatlined at a low level in most other countries, or fallen in the case of Sweden.

And as our new survey published by Ipsos MORI shows, this trend remains stable. The switch from a negative balance of opinion to a positive one started before the 2016 referendum on EU membership, in the middle of 2015 – but it did gain pace after.

Reassurance and regret

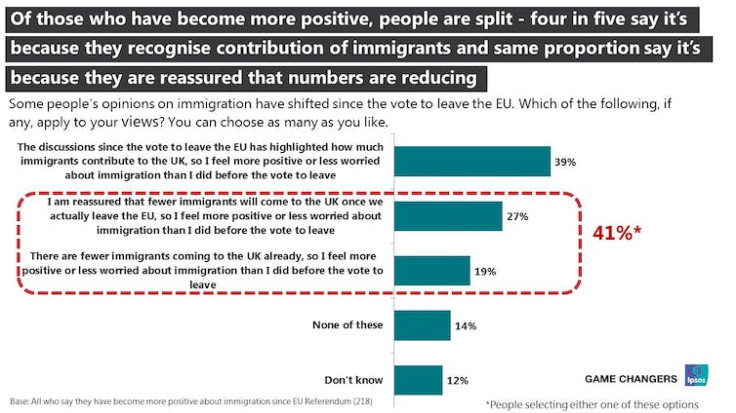

There are two broad explanations for why this is happening – that the change is being driven by “reassurance”, or “regret”.

The first is the idea that people feel they can now say that immigration has positive aspects, because numbers are coming down, or they believe numbers will be lower in the future, as a result of Brexit.

Regret, on the other hand, could be driven by a realisation of what we’re losing from lower immigration: as numbers fall and warnings of skills shortages and economic impacts increase, the extent to which the country benefits from immigration becomes more obvious.

Clearly these are simplifications – there are other explanations and these are not mutually exclusive views. But in our latest survey, we tried to assess the balance between these two explanations for the first time, by simply asking people why they are more positive.

And as the chart below shows, there is an almost perfect balance between the two explanations: around four in ten say they’re more aware of the contribution that immigrants make, and the same proportion say they’re reassured numbers are falling or will fall.

An emotive debate

As with so much about immigration attitudes, there is no one clear answer or view, and therefore no clear indication for future policy and political direction. The very real trends of increased positivity actually give the government little clue as to whether they should loosen their drive to control numbers, or stick to their guns on the “hostile environment” immigration policy that has come in for so much criticism in recent months.

Immigration is well recognised as a polarising issue, and one of the key topics in a referendum vote that split the country down the middle.

But what’s more often missed is that our views are also full of nuance and contradiction. There are not just two immovable and monolithic pro- and anti-immigration blocs, as shown by our previous research, and another of our just released polls for the Evening Standard. For example, the majority of the public would like to see the government’s cap on the number of doctors coming to the UK from outside the EU lifted entirely or increased – but the majority support the cap, or even greater restrictions, on computer scientists.

One thing seems clear – British people’s increased positive outlook seems to be little to do with the Brexit debate leading people to be better informed on immigration facts, at least on key aspects like the scale of immigration. When we asked what percentage of the population immigrants make up, which we’ve done regularly over many years, the average guess was 28%, compared with a reality of around 13%: we are just as wrong as we’ve always been.

Of course, this is because our emotions colour our views of scale as much as the other way round. The immigration debate remains an emotive one, caught up in our identity, culture and values more than cold calculations.

But all these challenges don’t mean that attitudes to immigration should be ignored in setting immigration policy. There is a case that Brexit was partly a result of ignoring immigration concerns, rather than either acting to reassure people, or challenging their views.

With a white paper on the post-Brexit immigration system now expected by July, the risk for the government comes not from listening to apparently fickle and contradictory public opinion, it comes from mishearing or caricaturing it – again.

Bobby Duffy, Visiting Senior Research Fellow, King's College London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.