Return Of Saddam-era Archive To Iraq Opens Debate, Old Wounds

A trove of Saddam-era files secretly returned to Iraq has pried open the country's painful past, prompting hopes some may learn the fate of long-lost relatives along with fears of new bloodshed.

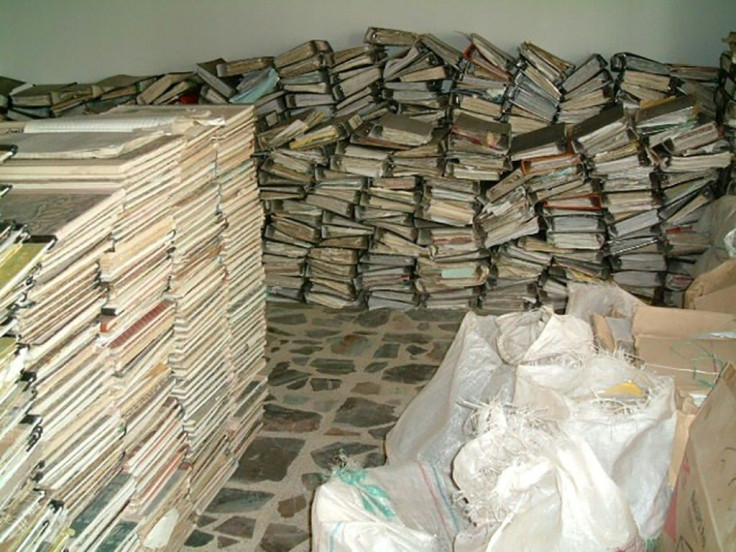

The five million pages of internal Baath Party documents were found in 2003, just months after the US-led invasion that toppled Saddam, in the party's partly-flooded headquarters in tumultuous Baghdad.

Two men were called in by confused American troops to decipher the Arabic files. One was Kanan Makiya, a long-time opposition archivist, the other was Mustafa al-Kadhemi, then a writer and activist, and now Iraq's prime minister.

"With flashlights, because the electricity was out, we entered the waterlogged basement," Makiya told AFP by phone from the US. "Mustafa and I were reading through these documents and realised we had stumbled upon something huge."

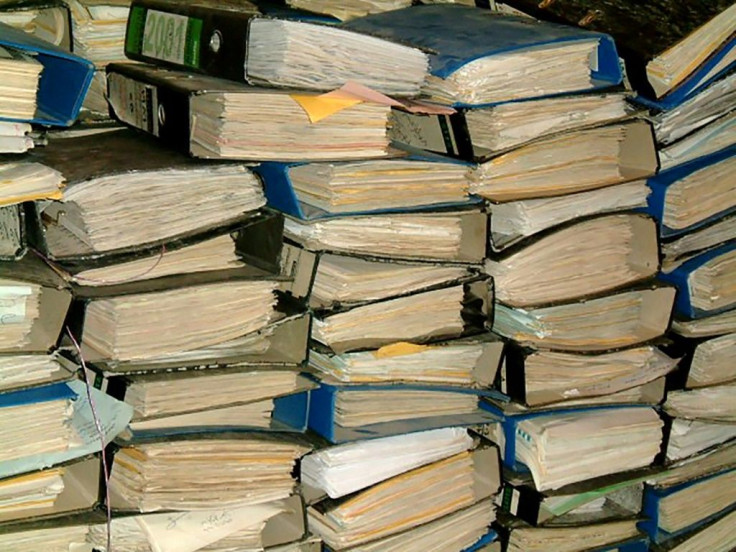

There were Baath membership files and letters between the party and ministries on administrative affairs, but also reports from regular Iraqis who were accusing their neighbours of criticising Saddam.

Other papers raised suspicions that relatives of Iraqi soldiers taken prisoner during the 1980-1988 war with Iran were potential traitors.

As sectarian violence ramped up in Baghdad after the US-led invasion, Makiya agreed with occupation force authorities to transfer the massive archive to the US, a move that has remained controversial.

The documents were digitised and stored at the Hoover Institution, a conservative-leaning think tank at Stanford University, with access restricted to researchers on-site.

But on August 31, the full 48 tonnes of documents were quietly flown back to Baghdad and immediately tucked away in an undisclosed location, a top Iraqi official told AFP.

Neither government announced the transfer, and Baghdad is not planning to open the archive to the public, the official said.

This could disappoint the thousands of families who may have a personal stake in the archive's contents.

"Saddam destroyed Iraq's people -- you can't just keep quiet on something like that," said Ayyoub Al-Zaidy, 31, whose father Sabar went missing after being drafted for Iraq's 1991 invasion of Kuwait.

The family was never given notice of his death or capture and hopes the Baath archive could hold a clue.

"Maybe these documents are the beginning of a thread that we can follow to know if he's still alive," said Ayyoub's 51-year-old mother Hasina.

She spent the 1990s pleading with the Baath-dominated regime for information on her husband's whereabouts, and holds little hope of more transparency now.

"At this rate, I'll be dead before they make them public."

Some argue the archive could help Iraq prevent its blood-stained history from repeating itself.

"Many kids nowadays say 'Saddam was good,'" Murtadha Faisal, an Iraqi filmmaker, told AFP.

Faisal was 12 days old when his father was arrested in the holy city of Najaf during a 1991 uprising. He has not been heard from since.

He wants the archives opened to end any rosy nostalgia or revisionism about Baath rule, which some have praised compared to today's instability under a fragmented political class.

"People should realise how not to create another dictator," he said. "It's already happening -- we have a lot of small dictators today."

Divisions over the Baath's legacy still run deep, and some of its defenders argue the archives would serve to exonerate Saddam's rule.

"Making the archives public would prove the Baath party was patriotic," insisted a former low-ranking party member in comments to AFP.

Those fault lines are precisely what makes the archive's return a "reckless" move, said Abbas Kadhim, the Iraq Initiative Director at the Atlantic Council.

"Iraq is not ready. It has not started a process of reconciliation that would allow this archive to play a role," said Kadhim, who pored over the documents to write several academic books on Iraqi history and society.

What he found even implicated current officials, he said.

"Baathists documented everything, from a joke to an execution. Politicians, tribal leaders, people in the street will begin to use it against one another," he added.

Others say the files could be redacted to make them less inflammatory, but still accessible to local academics.

"The least we can do is have them available to Iraqi researchers the same way they were to American ones," said Marsin Alshamary, an incoming fellow at the US-based Brookings Institute who also used the archive for her PhD.

The US remains in possession of several archives seized after the 2003 invasion, including "even more dangerous government files," a second Iraqi official told AFP.

One day, Makiya hopes, all the blood-stained events retold in these documents will be part of Iraq's distant past.

"We can't remember the glories of 'the land between the two rivers' and the Abbasid empire, and forget the 35 years of actual horror that modern Iraq lived through," he told AFP.

"That is as much a part of what it means to be an Iraqi today as those romantic things."