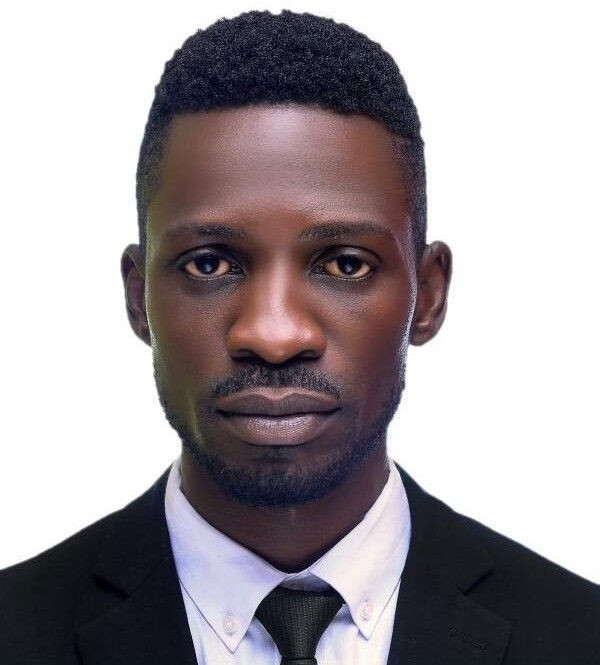

Uganda: Who is Bobi Wine and why is he creating such a fuss?

Ugandan singer turned politician Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, known as Bobi Wine, is at the centre of a storm in the East African nation. Ssentamu has been arrested and charged with treason in a civilian court – shortly after a military court dropped a charge of illegal possession of firearms and released him from custody. The 36-year-old uses his politically charged songs to call for change in the country that President Yoweri Museveni has led for more than three decades. The Conversation Africa asked Jimmy Spire Ssentongo to try and make sense of what’s happening.

How would you describe the public reaction to the political crisis in Uganda?

The public reaction is mostly a mixture of anger and shock. It’s true that Museveni isn’t known to be soft on his opponents or perceived threats. Nevertheless many Ugandans didn’t expect him to stoop this low. Given Bobi Wine’s growing popularity, most people indeed expected the state to act. After all, it routinely meted out retribution against key opposition figure Dr Kiiza Besigye.

But it was nevertheless shocking that the state would reach the point of laughably parading arms as evidence against Bobi Wine for treason.

The sense of shock can also be read in the loud silence of most government officials. Just a handful are offering to be part of the collective responsibility for the international embarrassment. It has been left to the president to offer explanations on social media where he’s been more active than ever before.

The public anger needs no elaboration. It can be seen, it can be heard, it can be sensed in various expressions on social media, on the streets, in places of worship and on radio, TV, buses, taxis and in homes. It’s also clear that the state is aware of the potential for a violent public reaction to the brutality and poorly staged justification for blatant political persecution. In anticipation, there’s been a heavy deployment of police and soldiers.

Since the passing of the Public Order Management Act (2013), demonstrators are treated as criminals. But in the heat of the current anger, this has not stopped people from defiantly using the limited space available.

Much of the anger has been channelled through social media. One simply needs to check the comments on the President’s Facebook posts to get a sense of the bitterness and public fury.

How serious a political challenge does Bobi Wine pose to Museveni?

This is best answered by understanding what Bobi Wine represents.

There’s a tendency to focus simplistically on Bobi Wine in terms of his moral, academic, and other experiential credentials. But this fails to place him contextually within Uganda’s political landscape.

Museveni is still popular among some section of Ugandans, who argue that in spite of his failings, he is still better than most of his seven predecessors. A lurking fear of “going back to the past” still plays in his favour. He has some achievements to show too.

But this narrative holds no sway with the younger generation, many of whom were born after 1986, the year Museveni became president.

Before entering formal politics, Bobi Wine enjoyed significant clout in the music industry. He entered the political arena through a defiant ghetto card with a relatively consistent background of politically critical music. Last year he stood for parliament, arriving on the political scene with a bang that surprised many. His catch phrase was:

Since parliament has failed to come to the ghetto, then we shall bring the ghetto to parliament.

The state’s panicky mistake was to react to his popular entry by openly persecuting him – initially through banning his music shows. Museveni showed early on that he’d noticed the young man had a following, by writing direct responses to him in the newspapers.

Then there was the ruckus in parliament over a vote to remove the age restriction on the presidency. Bobi Wine was among those who fought hard to stop it.

What seemed to draw Museveni’s attention even more was that candidates supported by Bobi Wine started to beat those backed by Museveni hands down.

Gradually Bobi Wine began to build a more conspicuous political identity around a very catchy slogan “people power, our power”, unmistakably dressing in red attire plus berets, emulating Julius Malema’s militant Economic Freedom Fighters party in South Africa.

It became clear that Bobi Wine was winning the hearts of youths as well as some earlier sceptics.

Given the widespread public desperation in Uganda, all many people want is a person who shows the potential of removing Museveni. All else is secondary.

In this sense Bobi Wine poses a real threat to Museveni, more so in consideration that young Ugandans, many of whom are unemployed, constitute a huge percentage of the active electorate.

Museveni has confronted numerous challenges and won hands down. How do you see this challenge playing out?

It is not clear how this might end. It largely depends on whether the state remains adamant, and which other players join Bobi’s cause.

The “Free Bobi Wine” agitation is developing into a movement that could easily take on a broader form.

It is also expected that Bobi Wine’s stature would have been greatly boosted by his imprisonment. The state has contributed immensely to his political weight and appeal while at the same time proving itself a political villain and international laughing stock. He will no doubt be reading the public mood.

Nevertheless, I don’t expect that the state is going to relent. Museveni is not known to countenance any threat. We are yet to see more of this roughness as we get closer to the 2021 elections, where there is strong reason to believe that Bobi Wine might stand.

What are the prospects for a more open democracy in Uganda?

Most institutions that would count in a democratic dispensation – parliament, the judiciary and an electoral system – exist in Uganda. But the country continues to show more signs of a hybrid state slanted towards presidentialism. Much of the real power to bring about change rests in the hands of the person who may not want to see it happen.

There is therefore every reason to believe that an open democracy is highly unlikely under Museveni, except certain elements of it that don’t threaten his hold on power.

Jimmy Spire Ssentongo, Jimmy Spire Ssentongo is an Associate Dean (Research and Publication), School of Postgraduate Studies and Research at Uganda Martyrs University, Uganda Martyrs University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.